As I See It with Bruce Helander – Once in a Lifetime

Feb 5, 2016

Although I was aware that Mother Nature had initiated one of the biggest blizzards in the New York weather record books, as a Florida resident it was still pretty shocking to see the perpetual white blanket of snow covering everything in sight as I looked out the window of the JetBlue aircraft began its descent to a just-cleared landing strip at LaGuardia Airport. I was in town to cover on behalf of The Huffington Post the Picasso Sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (that The New York Times called “…a once-in-a-lifetime event.”) and the Frank Stella retrospective at the new downtown location of the Whitney, as well as attend a reception for “Open This End: Contemporary Art from the Collection of Blake Byrne” at Columbia University. I was proud to have several vintage collages of mine included in this exhibition, as Byrne is considered one of America’s top collectors. He resides in Los Angeles, where recently he made the largest donation of contemporary art to the permanent collection of the MOCA, LA. It was a fascinating event, and included works by Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Mark Bradford, Marlene Dumas, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Mike Kelly, Martin Kippenberger, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Agnes Martin, Paul McCarthy, Juan Muñoz, Albert Oehlen, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Ed Ruscha, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol and Kehinde Wiley, among others.

Rubbing shoulders with curators, critics and the other artists in attendance, I was reminded of the famous lyrics from “Once in a Lifetime” by my friend and fellow RISD classmate, David Byrne of the Talking Heads, who poses the question: “And you may ask yourself—Well ...How did I get here? …And you may ask yourself, how do I work this?” And then I did indeed ask myself, how did I get here, and how did all these hotshots make it to the top to become household names in the art world? I once asked Robert Rauschenberg as I was curating a show of his work out of his Captiva Island studio for my gallery, what he considered to be the secret of success for an artist. His reply was that there was no secret, as he and everyone he knew who became famous, worked harder than anyone else, seven days a week, to achieve the polish, maturity, singularity and distinctive voice that are the necessary ingredients for a flourishing career.

I am reminded of the incredible but true story of abstract expressionist Harold Shapinsky, who had the good fortune to study with Motherwell and de Kooning and was included in a show titled “Fifteen Unknowns” at the celebrated Kootz Gallery in New York in 1950. Well-known artists of the gallery, including William Baziotes, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hofmann, and Robert Motherwell (who picked Shapinsky), all had their favorites, but of the fifteen emerging artists in the show, only Helen Frankenthaler and Shapinsky would eventually make a name for themselves. After this historic exhibition, Harold Shapinsky simply dropped out of sight, finding the art world to be superficial and competitive and he preferred to work alone in his studio every day, listening to jazz and smoking his pipe while his wife made ends meet by knitting sweaters for Bonwit Teller. But his seven-day work week commitment to his art-making in isolation for the next thirty years finally paid off, when the prominent London dealer James Mayor discovered him by chance, which led to a BBC one hour documentary about his life and his first one-man show at Mayor’s London gallery, which sold 22 works including a painting acquired by the Tate. There also was an article in The Observer by Salman Rushdie, which revealed Shapinsky’s background and extraordinary abstract expressionist painting to the world. Next came a special tribute evening at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. in 1985, an ARTnews and Newsday feature that brought even more fame, including a twenty-page story in The New Yorker. When I heard the story, I immediately invited him to have his first one-man show in the U.S. at my Worth Avenue gallery, which was attended by Peter Brant, mega art collector and owner of Art in America, and Henry Ford, to whom I made the first sale of Shapinsky’s work. Obviously, decades of devotion to his craft paid off like so many of the artists listed above.

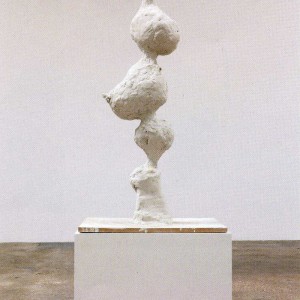

As the former editor-in-chief of The Art Economist, I established a column titled “Artists to Watch,” which predicted success based on the overall quality of their work, its uniqueness, the artist’s education and dedication, and the opinion of others. It was the most popular section in the magazine and many of our predictions of financial achievement and fame not only came true, but went through the roof. One of those early picks was Jacob Kassay, who created dynamic silver paintings that later were “cooked,” resulting in shimmering idiosyncratic surfaces. His first show sold out before it opened, and a long waiting list was established due to the buzz on the street. Then one of his paintings went to auction and sold over ten times the low estimate of $8,000. I’ve noticed the same kind of success with Cuban artist Kadir López Nieves, who a few years ago starting getting attention from visiting collectors for his adaptive reuse of classic 1950s American advertising tin signs, which are embellished with photographs and are battered, tattered and on occasion even riddled with bullet holes. The unique vintage imagery somehow caught the notice of The New York Times last year, and the rest is history. The work of Rebecca Warren, the British artist who stuck to her guns by aggressively producing remarkable, exaggerated, figurative, abstracted, oddball clay sculptures preposterously out of proportion but handsomely confident, seems to take a cue from some of the sculptures currently on display at MoMA’s Picasso exhibition. Another remarkable young talent is Kurt Knobelsdorf, to whom my pal the art dealer Gary Blakeslee introduced me. Knobelsdorf has the same genuine and uncommon charismatic imagery that has made stars of most of the artists in the Blake Byrne collection, and won several awards while at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The same winning combination is true with Greg Haberny and Steven Manolis, who I discovered during Art Miami this past December. The work of these artists had an immediate magnetic attraction to me, and I’d bet the farm that each of them soon will become well known. Haberny constructs gritty, spontaneous, obsessive abstract paintings that often have a slight narrative. His art is among the most unusual that I have seen in many moons, and I had my first chance to meet him during this New York visit, and I’m now convinced without a doubt of his eventual fame and fortune. His work, recently discovered and displayed by Banksy in London, cements his rising star. Manolis, who, like Shapinsky, has been refining his painting style over the last thirty years, is about to jump into the big time with his exquisite, large-scale abstract expressionist works that can hold their own next to any brand name non-narrative painter. With a stellar career as a former investment banker, he now has the necessary drive and ambition coupled with an innate aptitude for generating beautiful flowing pictures that have a delightful visual aroma reminiscent of Pollock, de Kooning and Kenneth Noland combined, with an unexpected twist. He was fortunate to study with Wolf Kahn, who had been taught by Hans Hoffmann. Not surprisingly, this studio workaholic already has been invited by a notable museum for a solo show opening later this year, and his paintings are selling like hotcakes. All of the artists mentioned above have experienced the ‘once in a lifetime’ syndrome and seem to share the same characteristics of natural talent and drive, which answers the question: “How did I get here?!”

Author

Bruce Helander

Bruce Helander is a former White House Fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts and is the former Editor-in-Chief of The Art Economist magazine. His columns on art, values, and investing in art appear regularly in The Huffington Post.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/As-I-See-It-with-Bruce-Helander-Once-in-a-Lifetime.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-Art-Lawyers-Diary-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-2-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/20231208_164023-scaled-e1714747141683.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/header.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-1-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/5-Questions-with-Alaina-Simone-1.jpg)