:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/header.jpg)

The Art Lawyer's Diary: Reflections on the 60th Venice Biennale: Foreigners Everywhere – Part I

Apr 26, 2024

By Barbara T. Hoffman

Without having paid much attention to the origin of the theme and title of the 60th Biennale, I assumed it to be a response to the movements to the far right in Europe and the United States stoked by fear of the "other,” the "different”. Thus, I anticipated a Biennale focused on a selection of artists who oppose the negative notions associated with the “other” in their work, including the economic and power structures that have created the current problems of migration fueled by poverty and war. For those unfamiliar with the Venice Biennale, the title and theme are set by the selected curator as the basis for the curatorial agenda and selection of artists in the curated exhibitions at the Giardini (321 in this Biennale) and the Arsenale and the 86 National Participations in the historic pavilions at the Giardini, the Arsenale, and city center of Venice and its surroundings. The term "foreigners everywhere” seemed to focus on the viewpoint of the observer rather than on the subject, the "foreigner.” Which accepts the indigenous or “other” as the foreigner.

However, after three days of exploring the national pavilions, the curated exhibitions, and the collateral events, I was stunned by the rich tapestry of imagination, ideas, intellectual musings, and multiple worldviews colliding to envision new futures to resolve the current global crisis. As John Akomfrah, the artist commissioned by the British Council, noted, in the final ensemble of installations in the pavilion of Great Britain, “Listening to the Rain,” iterations of acoustemology, which look at meaning and memorial from a different vantage point questioning the architectonics of the present and the specters of the past with the idea of listening and activism in mind, “I sense that one can know the world that you can find the name, and identity and a sense of belonging in this sonic.

John Akomfrah, Press Day Visitors “Listening all Night to the Rain” © 2024 British Pavillion**

In the same vein of optimism, the artists in the Nigerian pavilion express this sentiment: Nigeria Imaginary, the Nigerian Pavilion, explores the role of both great moments in Nigeria’s history – moments of optimism – and the Nigeria of the mind — a Nigeria that could be and is yet to be. Presenting different perspectives and constructed ideas, memories, and nostalgias of Nigeria, Nigeria Imaginary leverages an intergenerational and diasporic lens to imagine Nigeria for the future. These voices are articulated via diverse mediums, from painting, photography, and sculpture to AR, sound, and film.

This year's Biennale was curated by Adriano Pedrosa of Brazil, the first curator from the Southern Hemisphere. Like his processor of two years ago, the theme finds inspiration in a work of creativity. In this instance, the title "is drawn from a series of works made by the Paris-born and Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine since 2004”. The works are neon sculptures in different colors, each rendering the expression "Foreigners Everywhere" in a growing number of languages. The expression was, in turn, appropriated from the name of a collective from Turin that, in the early 2000s, fought racism and xenophobia in Italy: Stranieri Ovunque.

As Pedrosa stated, "The backdrop for the work is a world rife with multifarious crises concerning the movement and existence of people across countries, nations, territories, and borders. These crises reflect the perils and pitfalls of language, translation, and nationality, in turn highlighting differences and disparities conditioned by identity, nationality, race, gender, sexuality, freedom, and wealth. In this panorama, the expression "Foreigners Everywhere" has several meanings. First of all, it means that wherever you go and wherever you are, you will always encounter foreigners-they/we are everywhere. Second, it means that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.

“In Venice, foreigners are everywhere. Yet, one may also think of the expression as a motto, a slogan, a call to action, a cry of excitement, joy, or fear: Foreigners everywhere! More importantly, today, it assumes a critical signification in Europe, around the Mediterranean, and in the world, especially when the number of forcibly displaced people hit the highest in 2022, at 108.4 million, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and is expected to have grown even more in 2023.”

What differentiates this Biennale Arte 2024 is Pedrosa's focus on artists who are themselves foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporics, émigrés, exiled, or refugees-particularly those who have moved between the Global South and the Global North. Thus, he states, “Migration and decolonization are key themes here”. Pedrosa does not stop here, however, and uses “straniere,” another term in Italian for foreigners, to explore a second meaning, strange which then leads to queer.

Pedrosa further explains and justifies that “According to the American Heritage and the Oxford English dictionaries, the first meaning of the word “queer” is “strange,” and thus the exhibition unfolds and focuses on the production of other related subjects: the queer artist, who has moved within different sexualities and genders, often being persecuted or outlawed. Queer artists appear throughout the Exhibition and are also the subject of a large section in the Corderie.

The outsider artist, who is located at the margins of the art world, much like the self-taught artist, the folk artist, and the artista popular; and the Indigenous artist, who is frequently treated as a foreigner in their own land. The work of these four subjects is the focus of this Biennale Arte.”

Something else is also going on in the Biennale that apparently is a sea change in perception of the art world. I talked to many artists who traveled for the first time, indigenous artists from the Amazon who proudly spoke of a different worldview and aesthetic of equal value to solve our current crisis if “the other” would hear the message. In the past, Biennales focused on indigenous issues and brought forth voices not often heard by filmmakers and other artists; however, this Biennale presents the art of the “foreigner" as "art.”

Perhaps it is not surprising that the Biennale’s top prizes for the best artists participation in the curated exhibition went to the Mataaho Collective, which consists of four Māori women artists: Bridget Reweti, Erena Baker, Sarah Hudson, and Terri Te Tau. The Maori Mataaho Collective has created a luminous woven structure of straps that poetically crisscross the gallery space. Referring to matrilinear traditions of textiles with its womb-like cradle, the installation is both a cosmology and a shelter. Its impressive scale is a feat of engineering that was only made possible by the collective strength and creativity of the group. The dazzling pattern of shadows cast on the walls and floor harks back to ancestral techniques and gestures to future uses of such techniques.

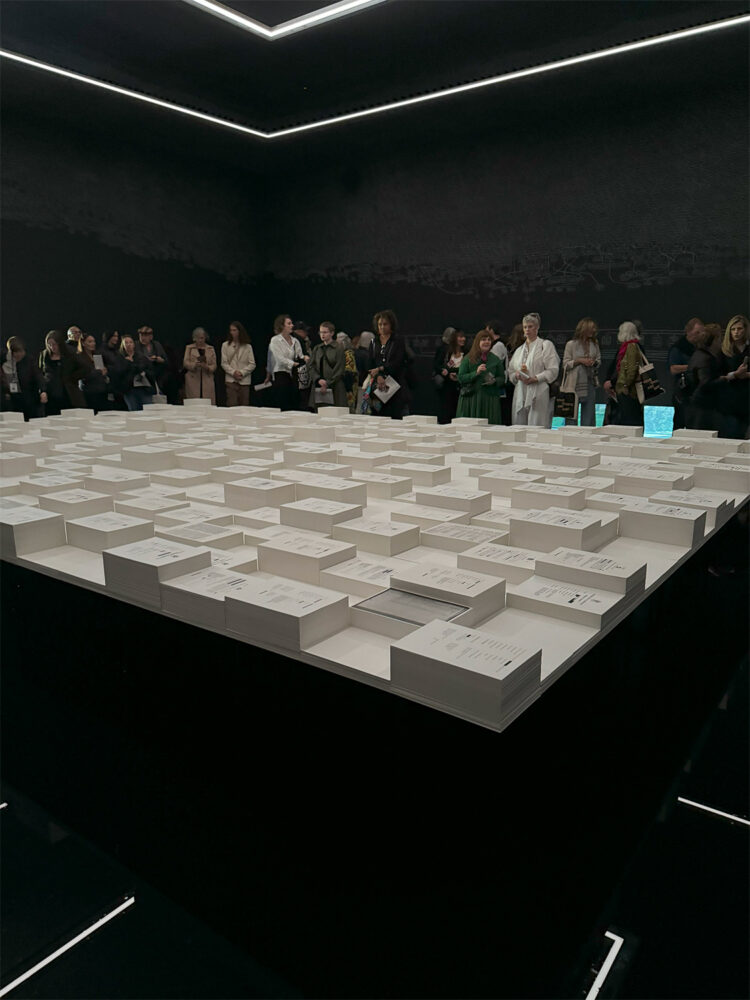

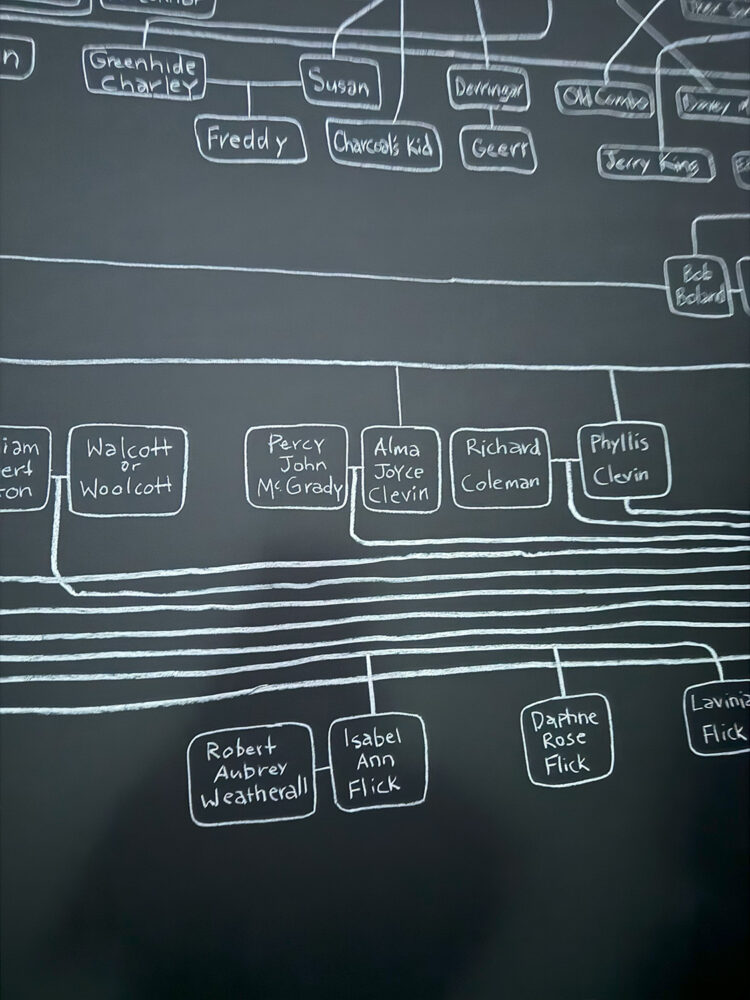

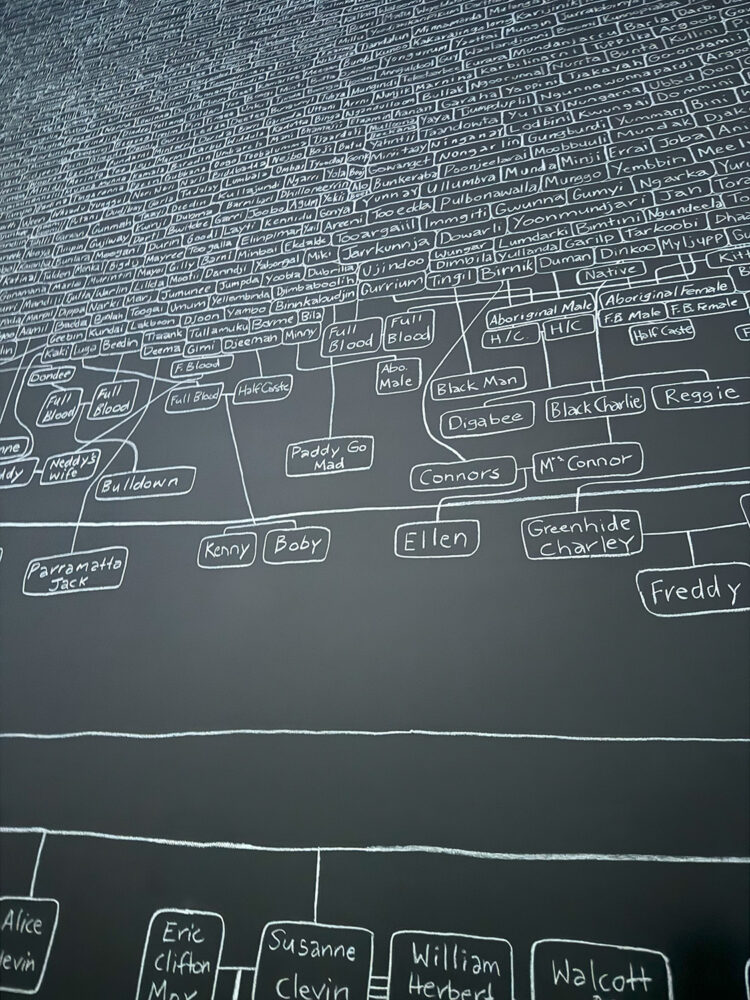

As a First Nation artist of Australia, Archie Moore won the Golden Lion prize for the best national pavilion for Kith and Kin. Although Moore is not the first First Nation artist to represent Australia, this is the first time Australia has won the Golden Lion. Moore created a genealogical chart with chalk on black walls tracing his British ancestors going back 65,000 years. In speaking of the work, Moore said, “Aboriginal kinship systems include all living things from the environment and a larger patchwork of relations. The land itself can be a mentor; we are all one and share a responsibility of care to all living things now and into the future”. While Moore’s thought represented and found expression in the world view of many of the Biennale artists, the judges seemed impressed by his technique of working in charcoal and the simple and elegant structure of the installation.

In selecting this quietly powerful pavilion, Archie Moore worked for months to hand-draw a monumental First Nations family tree with chalk. Thus, 65,000 years of history (both recorded and lost) are inscribed on the dark walls, as well as on the ceiling, asking viewers to fill in blanks and take in the inherent fragility of this mournful archive. Floating in a moat of water are redacted official State records, reflecting Moore’s intense research as well as the high rates of incarceration of First Nations people. This installation stands out for its strong aesthetic, lyricism, and invocation of shared loss for occluded pasts. With his inventory of thousands of names, Moore also offers a glimmer of possibility for recuperation.

Archie Moore, Kith and Kin © 2024 Giardini, Venice Biennale**

The art press has been diverse in its response to this Biennale. I refer to one specific critic, who largely seems to have raced through the Arsenale and largely thought the medium was the message. I refer to Arsenal Review: ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ Treads Familiar Ground, Freize April 182024 by Cloe Stead, who describes the Arsenale as “A textile and painting-heavy edition of the Venice Biennale'' and further argues that the “Venice Biennale follows a tried and tested method of curation…” With ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ unquestionably the most diverse biennial to date, I remain hopeful that, two years from now, we’ll get an exhibition that includes all these nationalities under a theme that doesn’t reduce them to the languages they speak, and the places they were born or moved to. Other more reflective and observant critics collectively state that “there has never been a Biennale like this.”

There is much to learn here, and there is no one-size-fits-all beyond the general themes stated above. For me, it is perhaps the first Biennale to be in tune not only with artists expressing the critical issues of their time, rather than the latest in marketable contemporary art aesthetics, but also deeply held values and world views that seek to use the lessons of the past, whether ancestors, a negative colonial experience or a religious world view and cosmology, to address a more positive future.

There is pride, not pessimism, and a recognition, too, of the contradictions inherent in the criticism of the global capitalist north. At the same time, there is pride in joining the “white box,” as expressed most strongly by the occupiers of the Dutch Pavilion, the Congolese Artist Collective Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolese (CATPC).

Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de plantation Congolaise, The International Celebration of Blasphemy and The Sacred

© 2024 Palazzo Canal 3121 Rio Tera Canal Dorsoduro**

The sculptures exhibited are made of clay from the remaining growths of old forests and are recast in cocoa and palm oil in Amsterdam. The collective stated, “Each sculpture will mark the passage from a painful and dark past to an ecological tomorrow, a future in which the Sacred Forest will flow through the pavilion.”

For the readers of One Art Nation, professionals in the art world, and collectors, the importance of the messages of this Biennale cannot be overlooked. Many artists, if not the majority, are exhibiting in Venice for the first time. The importance of the historic moment for the pavilions and the artist cannot be overstated. I was so moved to hear Jeffrey Gibson of the US express his emotions about being the first native American to represent the United States and the importance to his people and Native Americans to represent a country that by law had tried to eliminate them as a people and culture.

Jefffrey Gibson, Interior of US Pavillion, © 2024 Venice Biennale**

Julian Creuzet, a French artist from Martinique, is also the first from a French former colony to represent France. Both Creuset and Gibson are established artists with successful careers. Creuset, who was commissioned for the Performa 2023 Biennale in New York, asks, “What does the center mean when you are French? What is the meaning of the French pavilion in Venice and national representation? How do you construe all of that when they call you an overseas citizen, someone aware of being a part of a much more complex French story?”. Creuzet decided immediately on leaning his selection to make openness, joy, hospitality, and dialogue a key element of the pavilion experience, characteristics of his life in Martinique (6) Creuzet.

This Biennale informs not only about new artistic trends in art making but it links the art world to legal and global changes in the international area regarding traditional knowledge, climate change, migration, and other areas in which developments are largely unknown to the insular art world. For example, the UN’s goals for sustainable development reflect a new emphasis on culture as a fourth pillar of sustainable development.

Barbara Hoffman, Orlan, Jillian Crezet in front of French Pavillion, Attila cataracte ta source aux pieds des pitons verts finira dans la grande mer gouffre bleu nous noyâmes dans les larmes marées de la lune © 2024 Giardini, Venice Biennale**

In a recent presentation I made on behalf of ICOMOS at a preparatory conference to the G2 Cultural minister meeting in Brazil, I stated that the following principles guide G20 policy:

- Acknowledge the rights of Indigenous Peoples as established under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2007)

- Affirm that Indigenous Peoples have rights over their traditional knowledge, traditional cultural expressions, genetic resources, and associated intellectual property rights. (Article 31 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

- Recognize and incorporate Indigenous heritage action in the face of widespread climate change, which includes working, where appropriate and feasible, with Indigenous communities to anticipate, assess, and help manage worsening and future climate impacts on their heritage

- Embrace the principle of free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous communities before adopting measures concerning their cultural heritage. (ICOMOS Buenos Aires Declaration 2018).

- Acknowledge the rights of Indigenous Peoples to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage and to define and implement the best methods to conserve heritage of significance to their culture.

- Recognize that cultural and natural values are inseparably interwoven for Indigenous Peoples and should be managed and protected holistically.

- Recognize Indigenous sovereignty and control over their land and knowledge when seeking to use Indigenous knowledge as part of effective climate responses and initiatives.

- Promote the need for culturally appropriate Intellectual Property clauses when engaging with and sharing Indigenous Knowledge or TK.

My Brazilian colleagues further urged that any declaration of the G20 to issue from this year’s conference in Brazil address the following;

- Consider the deep interconnection between indigenous peoples’ tangible and intangible culture, in the ongoing digital planning and information processes to which these communities have been passively added.

- Value the heritage of Afro-descendants and their knowledge, memories, and places as cultural heritage, including Quilombola communities, ensuring the rights of these peoples.

- Valorization of forms of popular expression recognized as national heritage, such as music and dances (samba, choro, frevo, etc.) and gastronomy (artisan cheese, acarajé, etc.) operate consistently with the protection of traditional cultural expressions and expressions of folklore, respecting that for many traditional communities, their knowledge and cultural expressions form an indivisible part of their holistic identity. See the presentation by ICOMOS at the G20 Culture Working Group: Culture, Digital Environment, and Copyright.

UNESCO adopted the World Heritage Convention in 1972, which links culture and nature. Organizations like ICAMOS have recently included principles of indigenous people’s rights and values in designating world heritage sites of importance to humanity.

In 1970, the United Nations Education and Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the “Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing Illicit Activities”, which deals with the obligation of signatories to return illicitly obtained art and cultural heritage.

The latter, the 1970 convention, deals with the obligations of signatories to return illicitly obtained objects and cultural heritage. The Dutch Pavilion, “The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred”, and Yinka Shonibare of the Nigerian Pavilion deal with this principle and the complexity involved in returning cultural heritage. Yinka Shonibare’s installation at the Nigerian Pavilion, as shown below, deals with the complexities of the return of cultural heritage work.

Yinka Shonibare, Nigeria Imaginary: Benin Expedition of 1897 © 2024 Palazzo Canal 3121 Rio Tera Canal Dorsoduro**

This Biennale is an example that all our worlds have porous boundaries: Ideas and change migrate as do people, even in spite of physical boundaries, whether between nations, institutions, or areas of practice. Can the art world be a model for correcting social injustice, climate action, and fostering global peace for a sustainable future when political institutions are failing?

Indeed, given the situation of the United States’ inability to engage in conversation, and given the situation at the level of academics in the United States, the Biennale represents the most positive steps forward in the art world’s ability to engage in positive dialogue and discussion.

Stay tuned; In the June issue, I will discuss my selections of several of the most interesting national pavilions, to include, Great Britain, Egypt, Nigeria, Germany, Brazil, France, Netherlands and Mongolia, with interviews from some of the artists both in the pavilions and the Arsenale, my preferred of the two curated exhibitions. Of course, as is my practice, look for practical tips to enjoy Venice including collateral exhibitions and restaurants.

Author

Barbara Hoffman

Barbara T. Hoffman is recognized internationally and nationally as one of the preeminent art, intellectual property, and cultural heritage lawyers. With more than forty years of practice in every aspect of the field, Hoffman has been acknowledged by her peers with leadership positions in the New York City Bar Association and International Bar Association, elected to Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers...

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-Art-Lawyers-Diary-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-2-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/20231208_164023-scaled-e1714747141683.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/header.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-1-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/5-Questions-with-Alaina-Simone-1.jpg)