Drawings in Transition: Hubert Phipps at the Center for Creative Education in West Palm Beach

Mar 29, 2018

One of the most talked about exhibitions in Palm Beach County this season was “Drawings for Sculpture,” produced by artist Hubert Phipps for the Gallery of the Center for Creative Education set in the historic neighborhood district of Northwood in West Palm Beach.

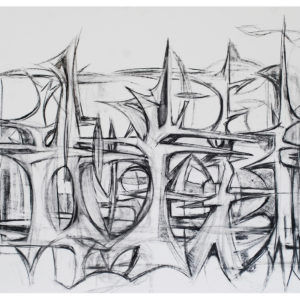

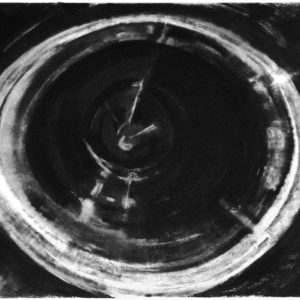

If you were not prepared fully in advance, you likely would be pleasantly surprised upon entering the main gallery to be confronted with one of the most bold and inventive black and white charcoal drawings that I have ever seen. This huge work on paper certainly lives up to its title Mystique, as it definitely is enigmatic and oddly spiritual at the same moment, and for many viewers, mesmerizing. This sensitive composition fits perfectly within the drawing parameters of Phipps’ show, as most of the studies could be compared to an architect’s blueprints where the sketches are eventually transferred to clay and then finally cast into bronze sculpture. So, it was quite provocative to view a totally conceptual picture, drawn and then erased, re-drawn and then “polished” over again by the artist (often with his feet and hands!), with other edges sharpened or toned down and some areas brightened and elongated, and yet this magnificent charcoal composition retained its integrity and mystery. This adds significantly to the visual drama of this handsome conceptual piece, which could almost be mistaken for a surrealist smoke signal rising from an Egyptian incense stick.

The handsome gallery, a former roller rink built in the 1950s, still retains some of its original wood flooring, and the tall exposed ceilings and iron support beams introduce yet another dimension to what is considered the best show of the season. Visitors were welcomed into the first exhibition space, which displayed Mystique next to a black baby grand piano that was a perfect match of form and function. A second “mystical” drawing, titled Dreamscape, was placed above the piano, which curiously built up an exciting visual energy and, forgive the pun, a sounding board where all the objects in the room seemed to work together in harmony.

Thousands of years ago, there is evidence of primitive humankind developing an affection for sculpted objects, oftentimes crafted out of wet clay or mud in all sorts of shapes, some of which were decorative and others simply utilitarian, such as a vessel for liquid or grain or even an earthen square brick that when multiplied would assist in building shelter. Later, as craft became more sophisticated and artists began sculpting forms in stone, it was more efficient to begin this long development process by carefully sketching out the object first, whether it be human or animal or organic, long before the actual construction of a sculpture began. Its important to note that legendary artists like Michelangelo would judiciously outline a sketch on a block grid that would serve as a blueprint for a much larger and ambitious final result. A good example of his early exploratory drawings is the figure studies for David, the 17-foot carved white Carrara marble statue still standing in Florence. The idea of beginning a project of this complexity without the initial studies, instead starting from scratch with a hammer and chisel, would be sheer madness.

So, the concept of creating drawings for sculpture was an accepted practice that became particularly popular during the Renaissance. The sketchbooks of Leonardo da Vinci are quite remarkable, as they not only included memorable charcoal studies for portraits that would be completed in the future, but in this case, served as a valuable collection of sketches for da Vinci’s inventions, from the concept of a helicopter (Hubert is a certified helicopter pilot) to a submarine. “If you could draw it, then you could make it,” became a kind of mantra for aspiring artists who wanted to breakout from conceptual drawing of objects to letting only the limits of their imagination guide them into prominence.

In what is considered a type of golden age of modern bronze sculptures, which began at the turn of the 19th century, many of the greatest artists of our time began to be recognized as historic innovators, whose influence continues to this day. Although the emphasis on Phipps’ exhibition certainly was on his preliminary and conceptual studies, the artist did present a modest overview of recent sculptural works, which offered an informative and satisfying comparison to the variety of drawings on display. Even on a moderate scale, the bronzes as shown in this exhibition were strong, interesting works that made a delightful comparative demonstration. These bronze sculptures of Phipps remind me of other works that have an arm’s length connection to many of the three-dimensional pieces on view at the CCE. Jacques Lipchitz, Figure, 1926 (MoMA), has its powerful beginnings in compelling sketches, as well as Henri Laurens’ La grande sirène 1945, a particularly delightful image of a bronze mermaid where you can sense the laborious test studies that shaped a masterpiece. I’m also reminded of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze Table (La table surréaliste), 1933 (Le Centre Pompidou), which relates to Phipps’ inventive stacked stainless steel pair of twin-like sculptures, Pieces of Six, 2015, and Pieces of Eight, 2016, that were among my favorites. For this handsome series, he decided to acquire bits and pieces of weathered metal geometric-shaped foundry fragments and then cast the pair of sculptural works into stainless steel, utilizing energy from the inventiveness of taking found objects and turning them into something expressive and convincing, which reminds me of Pablo Picasso’s bronze Woman with Baby Carriage, 1950 (Musée Picasso Paris), where the father of Cubism gathered pieces of junk metal that form a recognizable composition of a standing figure and a baby on wheels. Picasso loved discovering found objects, and like Hubert Phipps, could recognize at once the delicious possibilities at first glance. As a connective side story, Pablo and his girlfriend, Françoise Gilot, were known to wander around Paris pushing an empty baby carriage that he would fill with whatever promising bits and pieces of abandoned items that he responded to during their daily walks. Picasso’s most famous found object sculpture, Bull’s Head, 1942, was fashioned from a bicycle seat and handlebars that were highly abstract, but like Deborah Butterfield’s complicated found steel fabrications of life-size horses, these artists seem to create magical illusions with superior vision and ingenuity.

“Drawings for Sculpture” had its own magical presence at the Gallery of the Center for Creative Education, where Phipps mixed together the best of historic influences and the inherent grace of charcoal lines that seemed to develop a life of their own on the exhibition walls, exploding in character and individuality when placed next to the final evolution of drawings-into-three-dimensional objects.

For more information on the artist, please visit: www.hubertphipps.com.

Author

Bruce Helander

Bruce Helander is a former White House Fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts and is the former Editor-in-Chief of The Art Economist magazine. His columns on art, values, and investing in art appear regularly in The Huffington Post.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Drawings-in-Transition-Hubert-Phipps-at-the-Center-for-Creative-Education-in-West-Palm-Beach.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-Art-Lawyers-Diary-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-2-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/20231208_164023-scaled-e1714747141683.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/header.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-1-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/5-Questions-with-Alaina-Simone-1.jpg)