The Art Lawyer’s Diary: Lots of Smoke and No Fire as Goldsmith Prevails Against Warhol Foundation in the Supreme Court

May 24, 2023

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. No. 21-869.

This Art Lawyer’s Diary refocuses on an area of expertise and passion: the subject of artists and copyright, particularly the doctrine of fair use which is an affirmative defense to an artist’s copying another artist’s work without permission.

It is no surprise to my readers that I had written critically of the detour taken by the Second Circuit in Cariou v. Prince (2013), predetermining the ruling of the District Court in this case. In the September 2020 Art Lawyer’s Diary, I wrote on Warhol v. Goldsmith as the appeal of the clearly depressing district court decision was in process; the relevant excerpt follows and is useful source material for this issue which focuses on the takeaways from the Supreme Court decision.

The appellate court reversed the district court’s finding, and held that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph was not fair use. Each of the four factors weighed strongly in favor of Goldsmith. The Andy Warhol Foundation appealed the decision of the Second Circuit that Warhol’s use of the photograph of the singer Prince as basis for series of artwork was not protected as fair use under Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C.S. § 107, with respect to factor one, the Second Circuit stated that Warhol’s series was not transformative because it retained essential elements of photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements, notwithstanding a different message created by the style of appropriation and that “it’s a Warhol.”

The Decision

In a 7-2 opinion written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the Supreme Court affirmed the Second Circuit Appellate Court’s decision; however, the Supreme Court considered only one question. The question—as paraphrased by me—was whether stating “it’s a Warhol” is enough to conclude that factor one favors the appropriation artist on these facts. The question, as framed by the Court, was whether the Warhol Foundation established that its licensing of Orange Prince was a “transformative” use, and that §107(1) therefore weighs in their favor, simply by showing that the image can reasonably be perceived to convey a meaning or message different from that of Goldsmith’s original photograph of Prince.

Justice Sotomayor opined that the first fair use factor focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism. Although new expression may be relevant to whether a copying use has a sufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dispositive of the first factor. Here, while there may have been a different aesthetic, the Warhol Foundation’s use of Goldsmith’s previously unpublished image of Prince in a Warhol silkscreen print for licensing to Condé Nast was for the same purpose as Goldsmith’s image and competed with her licensing of that image…

The opinion is well worth a read for both lawyers and non-lawyers. While shedding light on a doctrine that had become increasingly murky and unpredictable over the years, largely based on the continuing expansion of the “transformative” concept as an analytical tool to determine “purpose and character” under factor one, the arguments on the merits in the opinion between the majority and dissent are remarkable on many levels. In some ways, they reflect that 59 amicus curiae briefs were submitted to the Court, almost equally divided in passion and law, between supporters of the Warhol Foundation and Goldsmith. As discussed below, the doom and gloom and apocalyptic vision predicted by the dissent and the Warhol Foundation find no support in this decision.

The Supreme Court’s last fair use decision was in 1994 in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., involving a rap parody recording and song "Pretty Woman" by 2 Live Crew; a parody of Roy Orbison’s rock ballad, “Oh, Pretty Woman.” The Court’s analysis made clear that the work not only had a new message and aesthetic, but was a parody. This requirement that a secondary use comment on the original work had long been a requirement of the fair use doctrine in the Second Circuit until it was jettisoned by the Second Circuit’s decision in Cariou v. Prince (2013) and fair use became a “famous artist” defense with nothing more needed.

Key Takeaways

1. The Supreme Court held that original works like Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection included the original author’s right to prepare derivative works that transformed the original. Goldsmith’s original photograph of famous musician Prince, and Warhol’s copying use of that photograph in “an image licensed for the same purpose that Goldsmith licensed the image,” violated that right reserved for Goldsmith. If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying. Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing. More generally, when commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger. This conclusion, I would argue, has been the law both prior to and after Campbell in the Second Circuit and others, until Cariou v. Prince. Ringgold v. BET (1997) is still good law. BET used Ringgold’s artwork for set dressing and for the same purpose Ringgold would have licensed her work. Ringgold would have licensed the poster for the same use. BET’s use was commercial, and it cut into Ringgold’s right to create and sell posters, and other derivative works. Thus, all factors favored Ringgold. ***

2. Patrick Cariou prevails in a rematch against Richard Prince on factor one and transformative use. The Supreme Court’s opinion states that the Second Circuit’s rejection of the idea that any secondary work that adds little more than a new aesthetic or expression to its source material is necessarily transformative. Contrary to the misapprehension of the dissent, it also accepts —correctly—that the meaning or message is relevant to, but not dispositive of, the transformative use inquiry. Adding the color purple was not sufficiently transformative for Warhol, nor is adding the color blue and a guitar sufficient for Prince.

3. The commercial purpose of the Warhol Foundation’s recent licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast was in direct competition with Goldsmith’s licensing. The fact that Condé Nast may not have chosen to license the Goldsmith over Orange Prince is not relevant to the Court. That reasoning, however, does not comment on Warhol’s other uses of the photograph embedded in his silkscreens, such as for display in a museum. In other words, the secondary work’s specific use of an unauthorized derivative work is what is relevant to the analysis.

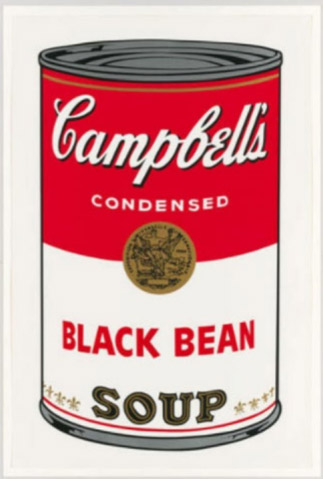

4. Using a Campbell Soup can logo, or another commodity logo, may still be fair use by artists. The Court clearly distinguished this use from the use of Goldsmith’s portrait, which, when incorporated as a reference by Warhol, was an unpublished photograph. The Court stated:

"The Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup. The use therefore does not supersede the objects of the advertising logo. Moreover, a further justification for Warhol’s use of Campbell’s logo is apparent. His Soup Cans series targets the logo. That is, the original copyrighted work is, at least in part, the object of Warhol’s commentary. It is the very nature of Campbell’s copyrighted logo—well known to the public, designed to be reproduced, and a symbol of an everyday item for mass consumption—that enables the commentary. Hence, the use of the copyrighted work not only serves a completely different purpose, to comment on consumerism rather than to advertise soup, it also “conjures up” the original work to “she[d] light” on the work itself, not just the subject of the work."

5. The Court rejects a bright line pass for all appropriation artists. Koons’s appropriations pass for fair use as long as there is parody. Both Rogers v. Koons and Blanch v. Koons remain good law. Notwithstanding the Warhol Foundation’s claims that affirmance of the lower court’s judgment would upset existing expectations concerning the proper analysis of infringement claims targeting visual art, the Court’s opinion makes it clear that this is not the case. First, courts have long recognized the fact-specific character of fair use analysis, and they have not always upheld fair use arguments advanced by34 famous appropriation artists. Compare, e.g., Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301, 304 (2d. Cir.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 934 (1992), with Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 251 (2d. Cir. 2006). Claims of fair use in the visual arts are governed by the same Copyright Act provision that applies to other modes of expression. 17 U.S.C. § 107. While the Warhol Foundation’s arguments developed in Cariou, and embodied for the first time in the Second Circuit decision, had that effect, the Supreme Court’s decision repudiates any such “bright line approach” to fair use, thereby leaving open many possibilities for artists who appropriate; including paying the appropriate license fee, commenting on the original in some way, or creating their own copy of an artifact for comment. Koons prevails, as would other artists, when the use would not be licensed for the same purpose, and the original is integrated for commentary on consumerism specifically, not necessarily for societal satire. The Court’s rejection of the Second Circuit’s factor one analysis in Cariou goes an enormous distance in clearing up the confusion attributed to the ever-expanding doctrine of transformative use.

6. The First Amendment is alive and well. Notwithstanding the doom and gloom of the dissent, artists are free to pay homage to iconic works of art history, and copyright law creates a breathing space to achieve the balance between encouraging artistic creativity while protecting the individual artist from unlawful appropriation. Limitations on copyright, such as the non-copyrightability of facts and ideas, still serve the intended purpose; and if not, as the concurring opinion states, that issue is one for Congress to address.

From the September 2020 Archive:

FAIR OR FOUL: PROTECTING CELEBRITY ARTISTS AT THE EXPENSE OF A CREATOR’S RIGHTS. ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION v GOLDSMITH (2nd Cir. 19-2420)

Oral argument in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in the Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith took place on September 15, 2020. In the lower court (The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al.) Judge Koeltl of the SDNY, incorrectly in my opinion, decided on a motion for summary judgment (there were no disputes as to the facts), that Andy Warhol’s silk screen images of Prince which copied noted portrait photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s image of Prince, did not constitute copyright infringement. On July 1, 2019, Judge Koeltl ruled that when Andy Warhol copied an unpublished photographic portrait of the late singer Prince, (allegedly provided to him by Vanity Fair as a resource), and created 16 different variations of the unpublished photo, that these were “fair use” and not copyright infringement. Plaintiff, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, immediately praised the decision saying “Warhol is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works.”

"Fair use" is a statutory affirmative defense to copyright infringement. 17 U.S.C. § 107. "The four factors identified by Congress as especially relevant in determining whether the use was fair are: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; (4) the effect on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work." The critical question in determining fair use is whether copyright law's goal of "promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts would be better served by allowing the use than by preventing it.” To make that determination, the Supreme Court has articulated in the case of Campbell v. Acuff Rose (1994) that one work transforms another when "the new work . . . adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” Although transformation is a key factor in fair use analysis under the first factor, whether a work is transformative is often a highly contentious topic, more often applied when it appears to justify a conclusion rather than operating as a bright line rule of law.

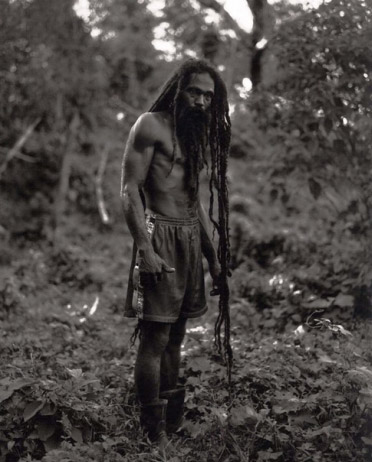

Of course, an artist’s celebrity status is not a factor to be considered under the weighing of the fair use factors under Section 107; for that misunderstanding, one needs to look at the sharply criticized and debated 2013 decision of the Second Circuit in Cariou v. Prince, its most recent articulation of the muddled and murky fair use doctrine. Cariou published Yes Rasta, a book of portraits and landscape photographs taken in Jamaica. Defendant celebrity appropriation artist Richard Prince who altered and incorporated several of plaintiff’s photographs into a series of paintings and collages called Canal Zone that was exhibited at a gallery and in the gallery’s exhibition catalog. The issue was whether defendant’s appropriation artwork, which incorporated the plaintiff’s original photographs, must comment on, relate to the historical context of, or critically refer back to the plaintiff’s original work in order to qualify for a fair use defense.

The Second Circuit found Prince’s uses to be fair, and that a secondary use does not need to comment on or critique the original in order to be transformative as long as it produces a new message. While Cariou’s book of 9 ½” x 12” black-and-white photographs depicted the serene natural beauty of Rastafarians and their environment, Prince’s work featured enormous collages on canvas that incorporated color and distorted human forms to create a radically different aesthetic. The Second Circuit found Prince’s work to be a transformative fair use of Cariou’s photographs. Whether or not art is transformative depends on how it may “reasonably be perceived, and not on the artist’s intentions.”

As a District Court Judge, Koeltl was bound to follow Cariou: in sum, the Prince Series works are transformative. They "have a different character, give [Goldsmith's] photograph a new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from [Goldsmith's]." See Cariou, 714 F.3d at 708. They add something new to the world of art and the public would be deprived of this contribution if the works could not be distributed. The first fair use factor accordingly weighs strongly in AWF's favor.

In finding Warhol’s use transformative, the circuit court denies protection to those elements of a photographic portrait that are protected by copyright law, as if the fair use defense to copyright infringement and the concept of celebrity transformative use literally erases “substantial similarity” and fails to appreciate how extensively Warhol’s silkscreen is derivative of – and a misappropriation of—protected expression from Lynn Goldsmith’s photographic portrait of Prince. It is difficult to reconcile the district court’s lack of solicitude for such camera-related choices in Goldsmith’s portrait of Prince with the Second Circuit’s 1992 decision in Rogers v. Koons, finding that “protectible elements of originality in a photograph may include posing the subjects, lighting, angle, selection of film and camera, evoking the desired expression, and almost any other variant involved.”

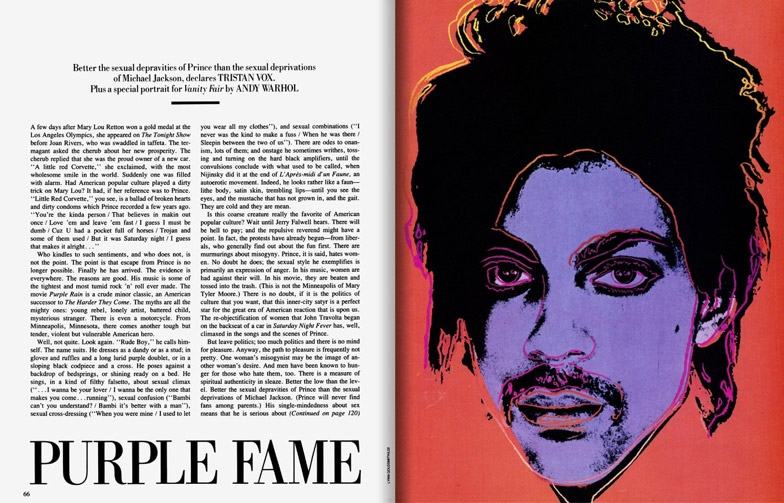

In October 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of Goldsmith's black-and-white studio portraits of Prince from her December 3, 1981 shoot (the "Goldsmith Prince Photograph") for $400. The article stated that it featured "a special portrait for Vanity Fair by ANDY WARHOL." The article contained a copyright attribution credit for the portrait as follows: "source photograph © 1984 by Lynn Goldsmith/LGI."

Based on the Goldsmith Prince Photograph, Warhol created the "Prince Series," comprised of sixteen distinct works — including the one used in Vanity Fair magazine — depicting Prince's head and a small portion of his neckline.

Prince died on April 21, 2016. The next day, Vanity Fair published an online copy of its November 1984 "Purple Fame" article, which had credited Warhol and Goldsmith for the Prince illustration in the article. Condé Nast then decided to issue a commemorative magazine titled "The Genius of Prince" and obtained a commercial license to use one of Warhol's Prince Series works as the magazine's cover. The magazine contained a copyright credit to Warhol but not to Goldsmith. Condé Nast published the magazine in May 2016.

Author

Barbara Hoffman

Barbara T. Hoffman is recognized internationally and nationally as one of the preeminent art, intellectual property, and cultural heritage lawyers. With more than forty years of practice in every aspect of the field, Hoffman has been acknowledged by her peers with leadership positions in the New York City Bar Association and International Bar Association, elected to Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers...

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/The-Art-Lawyers-Diary-Lots-of-Smoke-and-No-Fire-as-Goldsmith-Wins-Victory-in-the-Supreme-Court.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/The-Art-Lawyers-Diary-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-2-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/20231208_164023-scaled-e1714747141683.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/header.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/5-Questions-with-Bianca-Cutait-part-1-1.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/5-Questions-with-Alaina-Simone-1.jpg)