The Art Lawyer's Diary by Barbara Hoffman: A Movable Feast for a Troubled Time

Nov 14, 2025

How the Paris Art Scene Responds When Democracy Falters

I have returned to Paris often enough that the city is no longer a destination but a process of thinking. Arrival here is rarely neutral.

As a student in the late 60’s in Paris, I supplemented my undergraduate exposure as an art historian and French major immersed in the literature and philosophy of the past from Racine, Pascal, Voltaire, Moliere, Balzac, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Proust, Camus and Sartre, with the ground-breaking French philosophers and intellectuals of the time, several of whose classes I was privileged to attend.

Claude Levi-Strauss and Jean Piaget, believed that human thought and behavior are based on underlying, universal structures. They shared a “structuralist" approach, focusing on the interconnected systems and relationships that shape mental and cultural phenomena. Michel Foucault’s philosophical work focused on the idea that knowledge and power are inseparable. All ideas convey power that alters human behavior, and institutions primarily serve as organized attempts to manipulate individuals for particular ends. Foucault criticized historical Western classical-liberal norms for concealing power impositions under the guise of humanitarianism and rationalism. Roland Barthes asserted that the meaning of a text or work is not limited to the author’s intention. On the contrary, it is multiple, shifting, and nourished by the interpretations of readers/viewers.

French anthropologists, philosophers, psychologists, psychoanalysts, and poets - were radically changing how we understood the world, knowledge and humanism. These critical theories were intended to provide the philosophical underpinnings and tools for dealing with the traumas caused by colonialism, racism, homophobia, misogyny.

The 60’s and early 70’s were years of political trauma and uprising in France and the United States. For those who know the history, this is not the first time Paris has hosted the collision of art, law, and political upheaval. The spring of 1968 turned the Latin Quarter into a rehearsal studio for new forms of public life — not just protests, but posters, slogans, manifestos, improvised cinemas, print shops, and collective seeing.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated while I was in Paris during the events of 1968. Protests against racism, the war in Vietnam, attacks on homosexuals, and discrimination in employment and voting continued unabated.

These French writers offered and urged acceptance of the challenge to denaturalize social, aesthetic and linguistic norms and open up new ways of seeing and acting upon the world. The lesson is not that 1968 can be repeated. The lesson is that culture becomes political not when it demands agreement, but when it demands attention.

Paris in 2025 is not Paris in 1968. But the echo remains: art once again asks not what we think, but how we see.

Paris in October: The Movable Feast and the Work of Seeing

Paris has always been a stage for art, politics, memory, and spectacle, a city where institutions narrate history and the streets rehearse its future. To come in late October or November is to enter a season when the art world contracts and intensifies at once. Museums unveil major exhibitions; fairs garner their markets and rituals. Even ordinary looking may be reframed and charged with consequence.

Last year’s highlights were the successful recapture of the recently restored Grand Palais, an Art Nouveau exhibition hall originally built for the 1900 World’s Fair — by Art Basel Paris and my restoration to the status of Vip d’Honneur 10 am, with access en principe to a BMW; Mark Rothko, at The Foundation Louis Vuitton, and the 100th anniversary celebrating the birth of Surrealism at the Centre Pompidou. This year, the question was not whether Paris might offer escape from the attacks on democracy and the rule of law occurring elsewhere. The city of light does not promise refuge. Paris draws us, like a magnet to the moveable feast of our youth, an ever-shifting confluence of action and theory, its bright beacon illuminating for all who choose to observe the dynamics of power, institutional responsibility, and the role of art in a destabilized civic order.

To write from Paris in November 2025 is to write from a place where the spectacle of culture meets the machinery of law, where museums defend their relevance while markets define value faster than criticism can keep pace, and where the line between political event and cultural gesture grows thinner each season.

It is also inevitable as a lawyer/observer to write through the lens as someone trained to unearth facts and observe process, watch where power collects, and how it is justified, resisted, or manipulated. But in October 2025, the city felt less like an ideal and more like a mirror: a place where the same pressures facing cultural institutions elsewhere—censorship, market capture, donor influence, political oversight, public exhaustion—are not avoided but exposed.

The notes that follow are not a travelogue. They are a working record of how Paris stages the relationship between art and democracy at a time when both are under strain. In this season, the work of seeing is not passive. It is a civic act.

The Art Fair Circuit: Does the Marketplace Becomes a Forum?

Every October, Paris becomes the temporary capital of the global art market. What has come to be known as Paris Art Week is a choreography of VIP previews, tiered access, speculative buying, institutional courting, and rapid valuation. Access is currency here, and status appears not as taste but as architecture suspended on the cliff of theater.

Art Basel Paris (formerly FIAC) takes over the Grand Palais, and there are a host of satellite fairs: Paris Internationale and Asia Now in their tenth edition, as well as Offscreen in its fourth edition, are amongst my favorites. Offscreen, which highlights installations, still and moving images, was founded by Julien Freydman, the former Magnum, then Paris Photo director. The late Shigeko Kubota, pioneering Korean video artist was honored this year with an exhibition of video works, largely unknown in France. Offscreen was sited this year appropriately at the Chapelle Saint-Louis de la Salpêtrière, part of the historic complex founded by Louis XIV in 1656. It nudged out the Grand Palais as the most relevant architectural and politically resonant fair venue, in keeping with historical, aesthetic and philosophical themes of other exhibitions. The hospital is shrouded with a notorious history of the treatment of “mad women” and the diagnosis of hysteria in women. The latter is the legacy of nineteenth century Dr Jean-Martin Charcot whom the French recognize as the father of modern neurology. Charcot’s Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière (1876-80) is a landmark publication in medical photography. This collection of texts and photographs represents the female patients of Dr. Charcot at the Salpêtrière hospital and asylum during the years of his tenure as director. His classroom presentations of female hysteria in his patients became theater spectacle for “toute Paris”, including Toulouse Lautrec, and students, like Sigmund Freud, who translated his work into German. The Surrealists as well as artists like Egon Schiele were also influenced by these studies. The lens of French Theory, particularly, Michel Foucault, was relevant historically in 1968 and is today, to provide a narrative to understanding this institution of madness and hysteria. So to is Convulsive States (2023), by video and performance artist Liz Magic Laser. Her original installation and exhibition at Pioneer Square in 2023, critically and brilliantly explored the shaking body as both a symptom and a cure for psychic distress, in part, through the artifice of an hallucinatory investigative report that feverishly pursues the cure for hysteria as it uncovers mysteries at the Salpêtrière.

Offscreen offered many installations overtly or conceptually distinctly political charged. Not surprising, where the hospital’s control over bodies, women and other marginalized persons is embedded in the stones. The installation of Quentin Le Franc, which questions how art responds when democratic space contracts, seems particularly appropriate to the historical, social and cultural history of the site. The architecture serves as a framework, territory and playground for the works to create a dialogue between the historical context and installation.

The Art Basel brand is unapologetically and successfully associated with quality and commerce and the Grand Palais is a perfect site for its ambitions. Yet, and through no fault of the architecture, any sense of community and collegiality is in the imagination. To the extent the VIP program of FIAC (Frances’s signature contemporary and modern art fair for 47 years, before the takeover), promoted this community and salon of ideas, it is lost in this art world dominated by mega-fairs and mega-sales, largely, one might imagine, for investments. Basel Paris has still to learn about how physical not virtual community and conversations promotes sales and value. Paris’ satellite fairs thrive on something else: intimacy, inclusivity, experimentation, and belief in the potential and message of the artists represented.

Museums, Memory and the Politics of Exhibition

If fairs are where value is made, museums are where meaning is negotiated. This season, several major Paris institutions mounted exhibitions that engage directly—sometimes explicitly, sometimes obliquely—with the question of historical memory and democratic fragility.

Paris has never been a neutral ground for culture. Its primarily government funded institutions - Louvre, Pompidou, Musée d’Art Moderne, Quai d’Orsay, Palais de Tokyo - were built not just to preserve art, but to define what counts as art, what counts as history, and who is authorized to speak. Three major private collections add different voices and perspectives, through the exhibition of works of their owners, commissioned works and loans for exhibitions. These private museums and/or non-for-profit subsidiaries of luxury brands would not exist were it not for the luxury brands and the fortunes which fund their “owners” passions, tastes and exhibitions: The Cartier Foundation was founded in 1984; Bernard Arnault officially commissioned the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and the project was publicly announced in October 2006, after the concept and architect, Frank Gehry was selected in 2001; and the Pinault Collection founded 1999, Paris, 2021. All have block buster major exhibitions on view through January, with only the Cartier exhibition opening to coincide explicitly with the festivities of Paris Basel.

Whether by coincidence or confluence, I noted a synergy amongst the various exhibitions selected for this article. Perhaps it is the convergence of the 100th year of the birth of Surrealism and the 100th of Art Deco. In 1925, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris marked the peak of Art Deco. Decorators, manufacturers, magazines, department stores, artists, and even foreign nations competed fiercely to occupy Parisian buildings or erect temporary structures to display their latest creations, at or adjacent to the selected site, the Grand Palais.

The destabilization of the world order, attacks on the rule of law, the rise of fascism, conflicts, and genocide and the disappearance of facts as we know them, have provoked responses of the art world and the broader question of the role of the artist and art in these times. Several of the exhibitions may have been planned before the current threats to democracy and the fact that the world is increasingly divided into camps and an alternative universe. Yet, the artists and exhibitions on view provide remarkable and appropriate models for hope and transformation to a more equitable and harmonious world, whether such art is influenced and fuelled by poetry, imagination, Surrealism, French Theory, Buddhism or variants thereupon.

Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes were significantly influenced by Surrealism, particularly in its challenge to rational thought and traditional structures of meaning. Surrealism, through its emphasis on the unconscious, dreams, and "pure psychic automatism," sought to bypass conscious, rational control to access a deeper reality. This devaluation of the rational mind resonated with post-structuralist thinkers who critiqued the dominance of reason and objective truth in Western thought. Exhibitions in Paris reflect these historical trends of poetry and spirituality on the one hand and politics on the other.

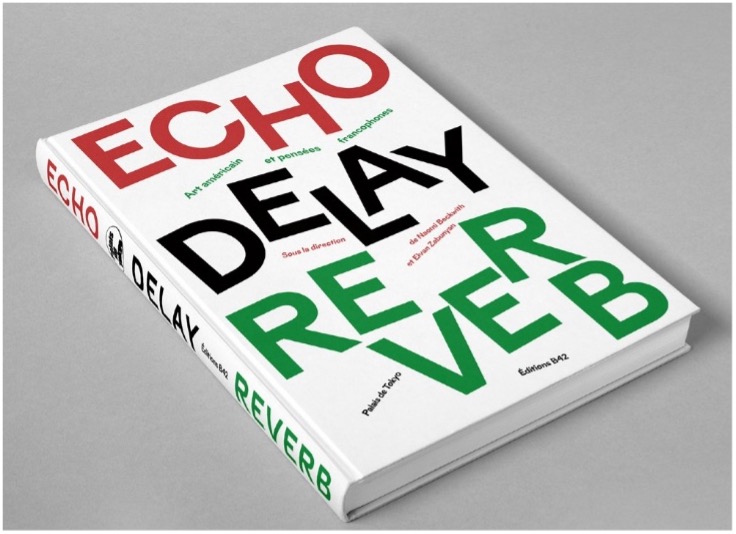

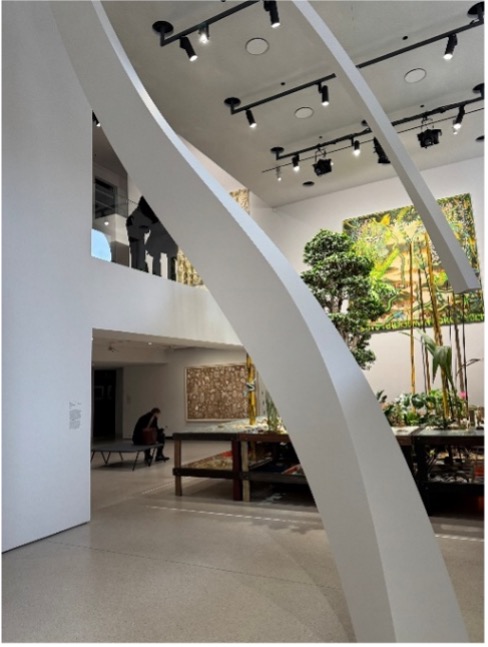

Palais de Tokyo — Echo, Delay, Reverb: American Art and Francophone Thought

22 October 2025 – 15 February 2026, Artistic Director Naomi Beckwith and Elvan Zabunyan

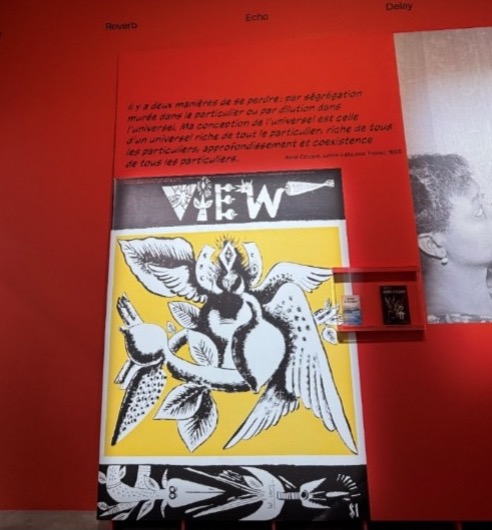

Curated as dialogue rather than thesis, it questions what happens when cultural history is not linear but recursive—when images return but are altered by power. Even though I participated as a law professor in an academic group originating at the Harvard Law School inspired by French Theory in the 1980’s, which included Professor Derrick Bell, the founder of critical race theory, I was unaware of the huge impact Beckwith claims for French Theory on United States artists and artistic practice, until her brilliantly conceived and ambitiously orchestrated exhibition, I was also unaware of the role played in the dissemination of French Theory by the Whitney Independent Study (ISP) Program. Beckwith is an alumna. The program has been suspended for next year by the chilling effect of President Trump’s attacks on wokeism and freedom of speech and artistic expression. In May, a performance involving Palestine was also cancelled.

The exhibition purports to show how artists in the United States catalyzed the revolutionary energies of thinkers who were by turn activists and poets – from Simon de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida to Frantz Fanon, Jean Genet, Aimé Césaire, Monique Wittig, Pierre Bourdieu and Edouard Glissant – to transgress genres and shift perspectives on the world today. Beckwith’s thesis is that reading the work of these authors helped artists in the United States to translate their ideas into unexpected forms and to forge tools with which critique institutions of the art world and of society as a whole. For them, theory has not been a gloss but a powerful impetus for denaturalizing social, aesthetic and linguistic norms and opening up new ways of seeing and acting upon the world.

A chilling effect has not prevented the excellent resource and text book, which accompanies the exhibition. This is not a catalogue, pays homage to Palestine and its flag in the colors red, black, white and green, is in memory of Felix Gonzalez Torres an alumnus of ISP who created an artwork on this theme, and is offered as a tool kit for resistance and hope in this chaotic time.

This work of Allora & Calzadilla references and pays homage to a meeting of which took place in Martinque in April 1941 between a group of artists and writers Andre Breton, Wifredo Lam and Claude Levi Strauss fleeing from occupied France, and Martinican poets Suzanne and Aime Cesaire.

Melvin Edwards — Palais de Tokyo

Part of the “Echo, Delay, Reverb” season

After Nazism, the Eurocentric conception of the human as a central value was challenged by many postwar philosophers.

Melvin Edwards, Homage to the Poet Léon-Gontran Damas, 1978-1981. View of the exhibition “Sarah Maldoror Cinéma Tricontinental”, Palais de Tokyo, (11/26/2021 - 03/20/2022) Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates (New York); Stephen Friedman Gallery (London); Gallery Buchholz (Berlin) © Melvin Edwards / ADAGP, Paris, 2025 Photo credit: Aurélien Mole

At the same time, Frantz Fanon, as well as the poets of Négritude—such as Aimé Césaire, with his Discourse on Colonialism (1950), Suzanne Césaire, and Léon-Gontran Damas—contributed to this critique of humanism by highlighting the dehumanizing character of the colonial and racist project that structures Western societies. Homage to his friend Damas is below. Mel Edwards was a close friend of the Négritude co-founder, the poet Léon-Gontran Damas from French Guiana, and dedicated a major five-part work, Homage to the Poet Léon-Gontran Damas (1978-1981), to him. This connection highlights the influence of Négritude's ideas, which centered on affirming Black identity and culture against the backdrop of French colonialism and universalism, on Edwards' practice. Edwards’ long-standing sculptural language—barbed wire, welded steel, forms evoking captivity and resistance—reads differently in 2025, when the question is no longer how violence is remembered, but how it is normalized.

The Poetics of Resistance: Beyond Identity, Beyond Didacticism

If the Palais de Tokyo tends toward theory—structural, academic, curatorial—another artistic response has emerged in Paris this season: a poetics rather than a manifesto. A turn toward imagination rather than argument. Not post-political, but post-didactic. Artists who refuse to reduce themselves to representation yet refuse to abandon the political stakes of the moment.

This is visible across several exhibitions, but most clearly in three figures whose work moves past identity categories into something speculative, visionary or poetic.

- Stephanie Jemison — artist-in-residence, Galeries Lafayette Anticipation

- Gerhard Richter — retrospective at Fondation Louis Vuitton

- George Condo — retrospective at Musée d’Art Moderne

Each confronts history without merely illustrating it; each invites viewers into a mode of attention that is not instructional but transformative.

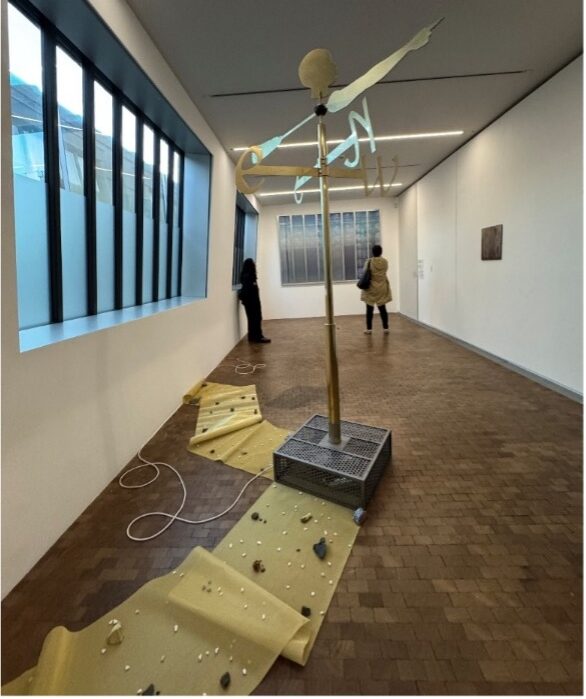

Stephanie Jemison — Galeries Lafayette Anticipation (2025–26 season)

Steffani Jemison, Exhibit: “Ciel clair / eaux troubles” (Clear Skies / Troubled Waters), Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, ©Lafayette Anticipations Oct. 2025**

Jemison’s work treats language, gesture and futurity as forms of refusal. Her films, texts and performances engage Afrofuturism not as fantasy but as method: a way to make space where dominant narratives refuse it.

Rather than depict identity, she disassembles it—turning the viewer from spectator into decoder. Jemison is one of the clearest reminders that art does not need to choose between politics and poetry; it can make politics legible only through poetry.

This installation is a powerful interweaving of physical phenomena with histories of Black liberation and political resistance. It transforms the gallery space into a site for profound reflection on the visible and invisible forces that shape human movement and memory. In 1831, Nat Turner, a plantation slave in Virginia, witnessed an eclipse, interpreting it as a sign for rebellion. Clear Skies/ Troubled Waters examines revolt and repression from 1831 to race riots in Boston Newark and Detroit in the summer of 1967 through natural phenomena (eclipses, wind patterns, variations in light and gravity).

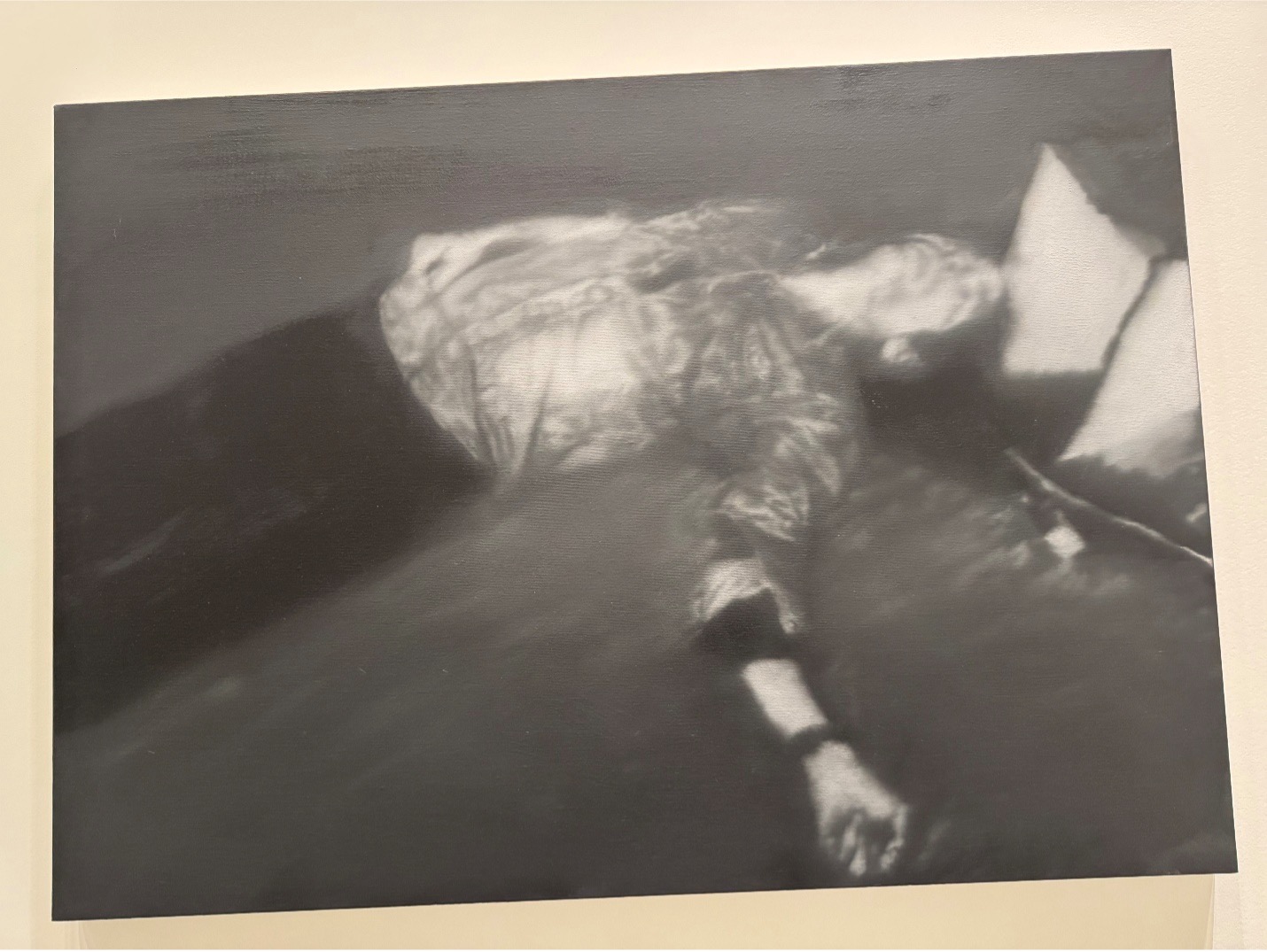

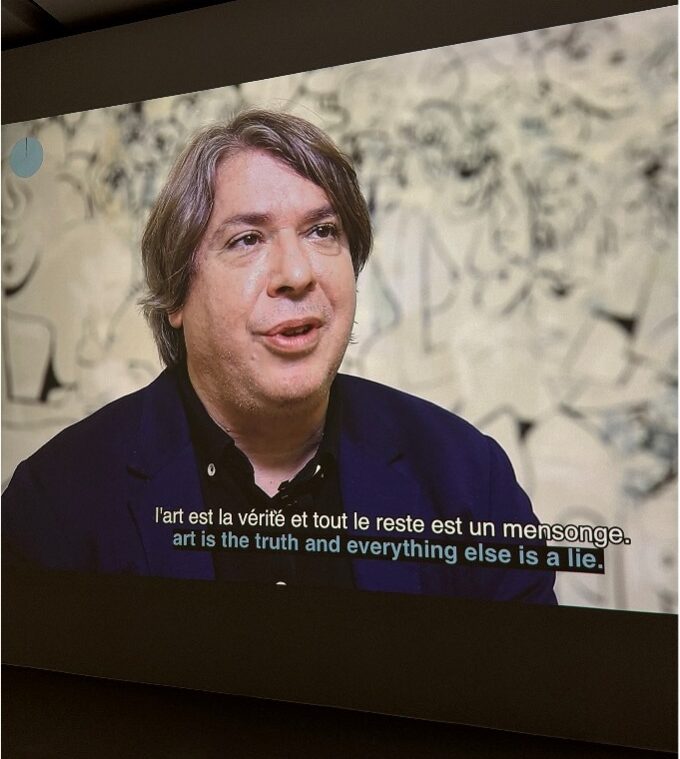

Gerhard Richter — Foundation Louis Vuitton

17 October 2025 – 2 March 2026

A six-decade retrospective, including the politically loaded 18 October 1977 cycle—Richter’s blurred images of the Red Army Faction suicides in German prison. Once controversial, now newly resonant in an age when state violence is both hyper-visible and structurally denied.

Richter famously said:

“Art is the highest form of hope.”

These are not contradictions. They are twin recognitions: that truth is fugitive, and hope requires form. Richter’s abstractions do not resolve history—they hold it in suspension.

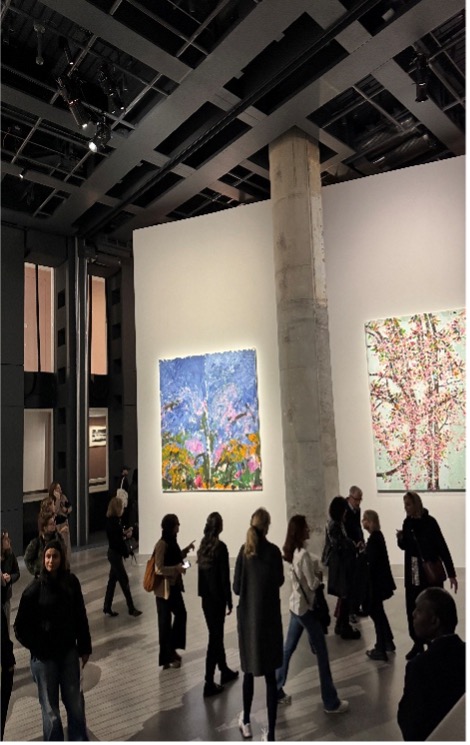

George Condo — Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

10 October 2025 – 8 February 2026

Condo’s Black Series—Expressionism twisted into psychological architecture—returns at a moment when fracture has become a global norm. His figures, distorted but unmistakably human, resemble not political portraits but the emotional ruins politics leaves behind.

If democracy is faltering, Condo’s paintings show the internal weather of that collapse. Not critique, but aftermath.

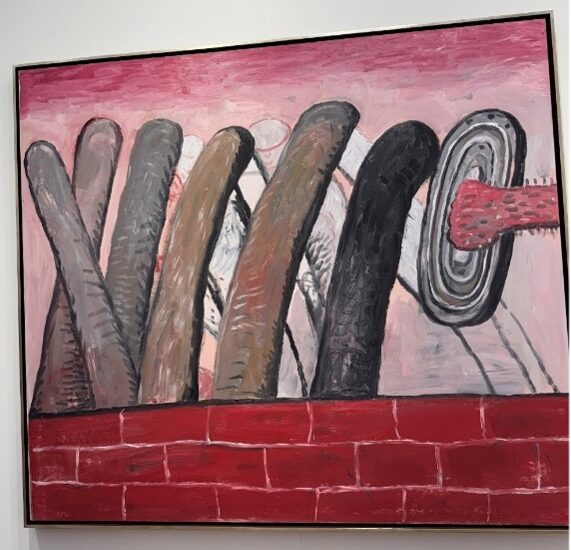

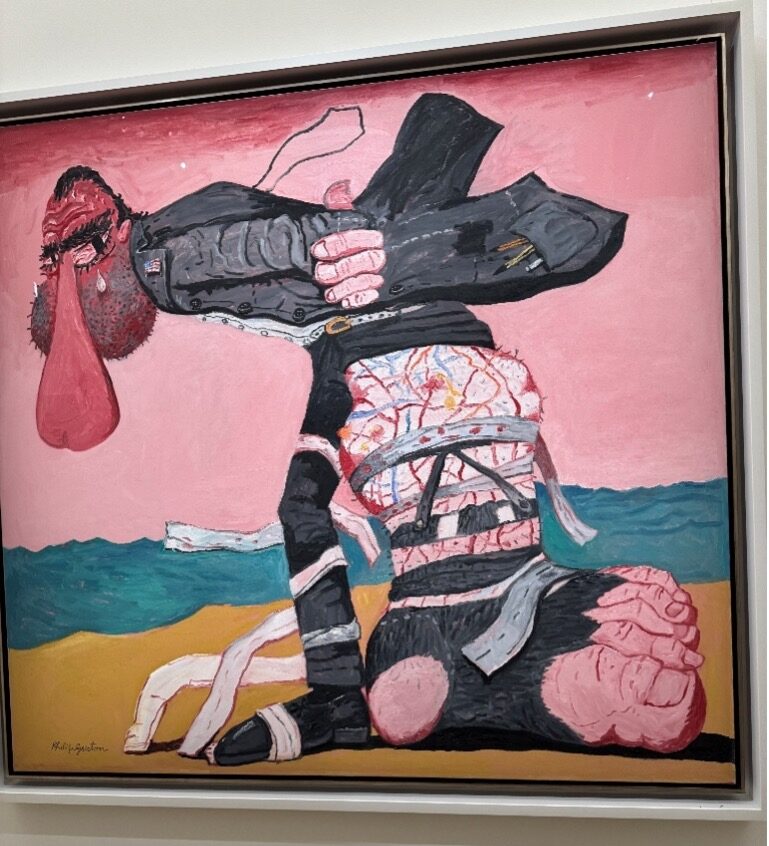

Philip Guston — Musée Picasso

14 October 2025 – 1 March 2026

Once delayed for fear of public controversy, the Guston exhibition now lands in a world where controversy is constant, and avoidance looks like complicity. The hooded figures return—not as symbols of race alone, but as warnings about what happens when violence goes unexamined long enough to become cartoon.

The museum now asks viewers not whether the work is offensive, but whether our unoffendedness has made us politically numb.

Architecture, Memory and the City as Argument

Paris is not just a city of exhibitions but of enacted arguments. Architecture functions here as a legal brief in stone—declaring what is private, what is public, what is preserved, and what is permitted to disappear.

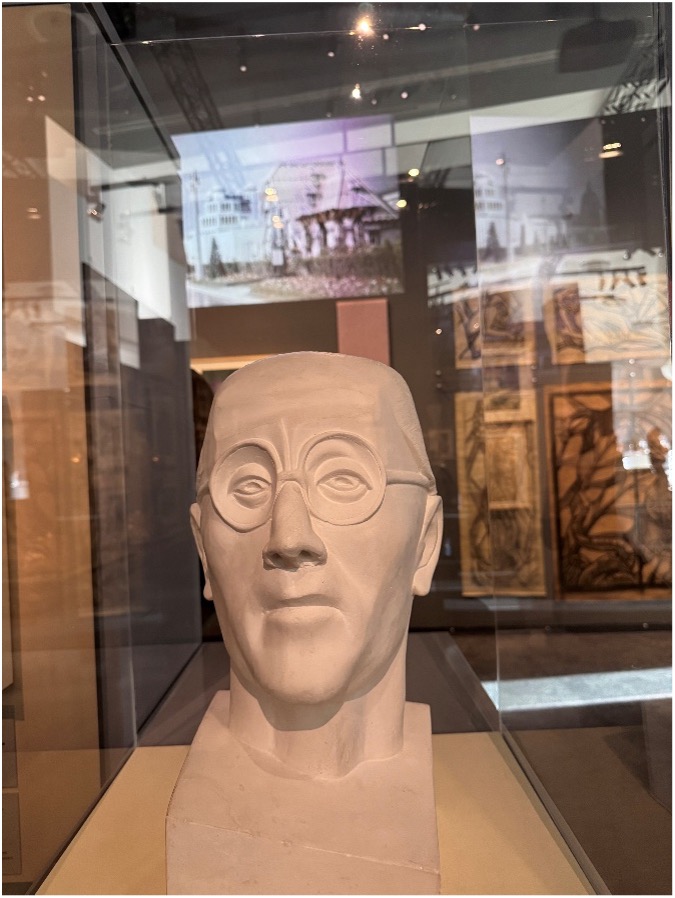

Cité de l’Architecture — Paris 1925: Art Deco and Its Architects

22 October 2025 – 29 March 2026

A centenary exhibition marking Art Deco not as nostalgia but as a reminder that style is never apolitical. Art Deco was the aesthetic of interwar optimism—and of rising authoritarianism. The show includes works by Le Corbusier and others whose visions of order now appear double-edged: utopian, and disciplining.

From 28 April to 30 November 1925, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs was held in Paris, on or near the grounds of the Grand Palais where each country presented its most emblematic achievements in the decorative arts in temporary pavilions.

There were two opposing architectural movements: the Art Deco style and the modernist movement, also known as the international avant-garde.

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret were given a plot of land behind the Grand Palais for their project. His model scandalized the organizers by its modernism and commitment to low-cost modular housing. He also submitted a radical plan of urbanism for redoing Paris.

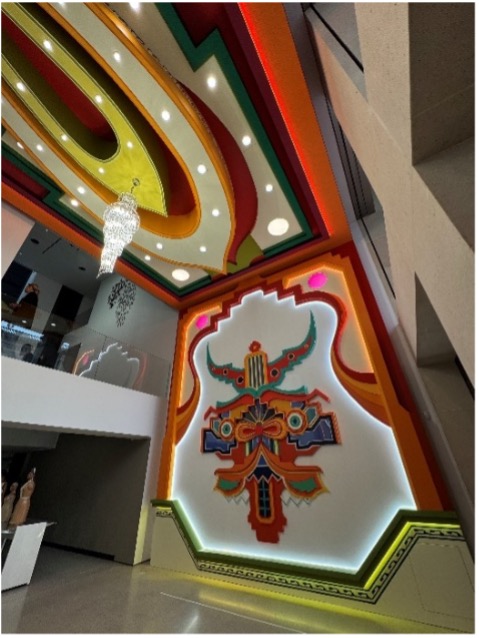

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain,

Exposition générale, August 23, 2026

Cartier’s new venue, 2 Place du Palais-Royal is a radical overhaul of the interior of the five-story Haussmann-era block, which was originally built in 1855 as the Grand Hôtel du Louvre, before becoming the Grands Magasins du Louvre. Jean Nouvel, also designed the foundation's previous iconic glass building on Boulevard Raspail. The inaugural exhibition, which opened October 25 showcases 40 years of the foundation's history through approximately 600 works by over 100 artists.

Nouvel’s design, once dismissed as spectacle, now reads as a proposition: museums must be legible from the outside or risk becoming citadels: glass, permeability, and civic transparency as architectural thesis. The design emphasizes openness to the city with vast bay windows and glass roofs, creating a "fishbowl-like effect" where the urban landscape becomes part of the exhibition experience. Nouvel made the 5 floors entirely movable, both walls and heights to suit an installation or an exhibition. For many of us, this caused a slightly panicked experience as the rationality of traditional architecture and structural design was no longer a guide to our trajectory and we struggled in the dark to find a path to the elevator or exit.

Perhaps that is the message: Democracy may involve chaos and lack of a clear path in its trade-off with authoritarianism. Freedom has a price. Democracy calls for attention. Looked at in another way, Ateliers Jean Nouvel studio director Mathieu Forest at the press preview explained, "It's unprecedented…Nothing is permanent – not the floor, not the walls, not the ceiling," he continued. "You visit and then next time you may have an entirely different perspective."

What is remarkably interesting in the current exhibition of commissions over the years, is its diversity in the selection of artists from around the world, diversity in medium and out-of-the-box thinking of contemporary art. This is not market-driven art. The architecture of Nouvel seeks to mirror its spirit: the collection is forward looking, inclusive and prescient of the direction of art to come in a world of rapid change, technology, AI and globalism, climate threats, and an uncertain future.

Pinault Collection — Bourse de Commerce

Minimal — 8 October 2025 – 19 January 2026

Maren Hassinger, River 1972/ 2011 (sculpture) with Dorothea Rockbourne Tropical Tan (1967-68), Pinault Collection, ©Pinault Collection Bourse de Commerce Oct. 2025**

The "Minimal exhibition at the Pinault Collection's Bourse de Commerce in Paris," explores the global and international evolution of this movement, which since the early 1960s, has radically reconsidered the status of artwork. As the catalogue states: the movement is characterized by an economy of means, pared-down aesthetics, and a reconsideration of the artwork’s placement in relation to the viewer. Artists across Asia, Europe, North and South America challenged traditional methods of display. This approach invited a more direct, bodily interaction with the art, integrating the viewer and the environment into the artwork itself.

The Minimal exhibition is a counterweight to the spectacle of the fair. Minimal stages quietness as resistance: works by Judd, Kawara, Ryman, LeWitt, Dorthea Rockbourne, Maren Hassinger and Howardena Pindell— pieces that refuse narrative, refuse speed, refuse distraction. In a season of overstimulated publics, the exhibition proposes attention as a political ace. As with Cartier, the exhibition, which is composed largely of Pinault’s collection, is avant-garde in the number of women artists over 50 who only recently have gained the prominence and market deserved.

If democracy depends on attention, then attention must be trained — slowly, deliberately, against the market’s velocity.

The American Parallel: 2024 and the Shrinking Democratic Imagination

Across the Atlantic, the 2024 U.S. election showed what happens when democracy is treated as spectacle instead of structure. Legal systems bent, norms disappeared, fiction and fantasy replaced facts, and institutions once thought stable became stage sets for power.

Since Trump’s Executive Orders, multiple American museums were attacked — not with fire, but with funding withdrawals, board interventions, legislative threats, and demands for “neutrality” that were anything but neutral. The cancellation of several Smithsonian exhibitions, would be based on my understanding of constitutional law for ten years in a law school, unconstitutional. The suspension of the ISP are unconstitutional but the current Court arguably has a different redacted copy of the Constitution and case reporters. As in the 1990’s a chilling effect has spread to cultural institutions: the ISP program has been cancelled for next year and a performance based on Palestine, cancelled in May.

Beyond discussion in this Diary, it would nevertheless be remiss to fail to mention that in New York, Philadelphia and elsewhere, there is "The Poetics of Resistance: Beyond Identity, Beyond Didacticism”. I mention in passing, the brilliant retrospectives, of Coco Fusco, Rashid Johnson, Wifredo Lam, Man Ray and the 100 years of Philadelphia to offer up vision as to art, politics and cultures can resist this moment of authoritarianism and provide a path to a democratic and inclusive future powered by imagination now.

Paris is not the escape from this condition. It is its reflection.

The Politics of Attendance

To attend an exhibition now is not a cultural act alone. It is a civic one. Showing up to the museum, the fair, the talk, the archive is a declaration that public space still matters, that meaning is not fully privatized, that art still functions as more than asset class or décor.

Absence, too, is political and institutions feel it.

In a world where attention is monetized, the decision to give it freely is a form of rebellion.

Conclusion — The Lawyer-Observer Writes from Paris

If critique is the labor of attention, hope is its companion. Not naïve hope, but procedural hope. Thekind that knows democracy is not guaranteed, that the law is not self-enforcing, that culture is not automatically public, but must be defended every season, every exhibition, every time we choose to look rather than scroll past.

Paris does not offer answers, only rehearsals.

It teaches us that art is not evidence, but inquiry. That museums are not mausoleums, but arguments. That fairs are not just markets, but weather reports for the emotional economy of a civilization under stress. That architecture remembers what politics forgets. That the work of seeing is still a public duty. That the poetry, meditation and imagination of artists like Coco Fusco, Jen de Nike and Stepfani Jemison can take us to another exterior level where alternative universes created by different facts transform at a level where the universe begins to acknowledge the oneness of all living beings and that we are all part of a giant ecosystem of life in the universe.

And so, the phrase returns, not as nostalgia but as instruction:

A movable feast.

Not a celebration, but a practice.

Not a refuge, but a rehearsal.

Not an escape from history, but a way of looking at it without surrender.

Art is the highest form of hope.

— Gerhard Richter, Documenta 7 in Kassel, 1982.

Author

Barbara Hoffman

Barbara T. Hoffman is recognized internationally and nationally as one of the preeminent art, intellectual property, and cultural heritage lawyers. With more than forty years of practice in every aspect of the field, Hoffman has been acknowledged by her peers with leadership positions in the New York City Bar Association and International Bar Association, elected to Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers...

Recommended Videos

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/ASF23-promo-pics-3222.jpg)

Charlie Manzo, Alaina Simone, Muys Snijders, Kyle McGrath, Caren Petersen, Jason Rulnick, Elysian McNiff Koglmeier, Bianca Cutait, Linda Mariano, Jack Mur

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=png)/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Insurance-Risk-Management-1.png)

Lawrence M. Shindell, Laura Patten, Ronald Fiamma, Mary Pontillo, Dennis M. Wade

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Banner-Image.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/20251205_124921-scaled.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/kian-lem-s_HqmrMsph8-unsplash-scaled-e1764007192632.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/5-Things-You-Should-Do-When-Buying-Art.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=webp)/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/sebastien-Laboureau-with-art-at-sagamore.jpg.webp)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Banner-Image.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=jpeg)/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Olga-de-Amaral.jpg)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=png)/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/webinar.png)

:sharpen(level=1):output(format=png)/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/sales-and-use-tax-dos-and-donts.png)